The Indian Contingent

About

The research process

In 2013 I was working for the Global Centre in Exeter, on a project on Exeter’s multi-cultural history. The project was called ‘Telling our Stories, Finding our Roots: Exeter’s Multi-cultural History’ – known as TOSFOR. You can find the website here.

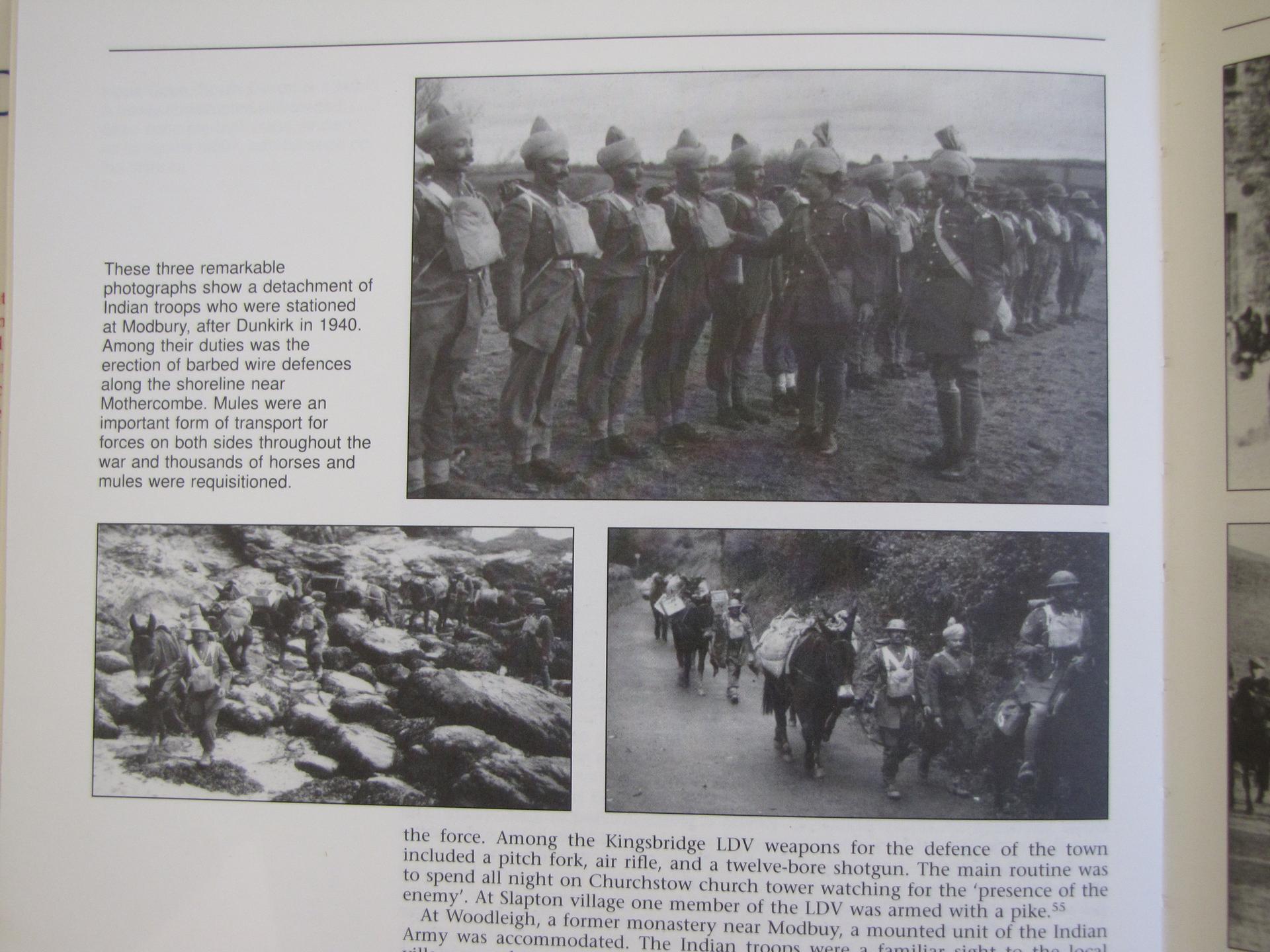

As part of that project, I was looking at a book called Devon at War by Gerald Wasley. In there I found these three photos:

Devon at War by Gerald Wasley

These photos were a surprise to me. I thought I knew about the Second World War, but I’d never imagined that there were Indian soldiers with turbans and mules in Devon. I interpreted the captions as meaning that they were on Dartmoor, but I later learnt that the photos were from St Austell.

I did some online research, and found a few references, most notably on the Commonwealth War Graves Commission website, on a page that is no longer available.

But I was intrigued.

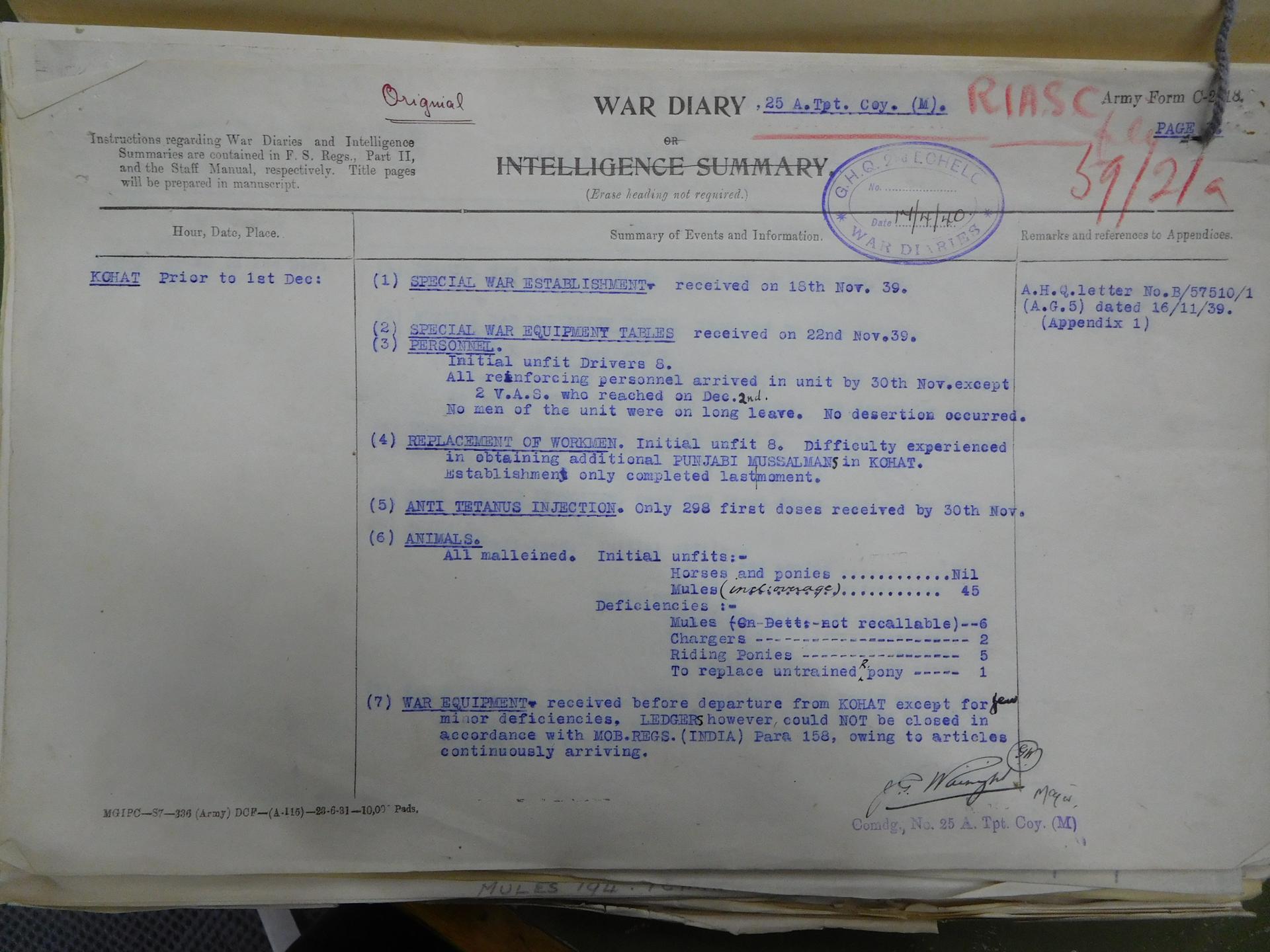

A few weeks later – on 25th February 2013 to be precise – I visited The National Archives in Kew to research various topics related to Exeter’s multi-cultural history. I had looked at the catalogue online, and easily found the K6 War Service Diaries for their time with the BEF in France (WO 167/1437 and sequence). I read the diary of the 25th Company, sitting in the hushed surroundings of the reading room.

The first page of the 25th Company’s War Service Diary

A War Service Diary is a strange document. It’s written every day by a unit’s commanding officer. Some were typed, some handwritten in pen or pencil. It usually contains dry details of who came and went on that day, deliveries, messages, statistics. Emotions rarely show through. But sometimes – if you know the context or if the pen slips – you can understand something of the human feelings behind the times, dates and places.

The 25th Company’s diary was mostly written by their Commanding Officer JG Wainwright. The story that unfolded, as I read on that late winter day in 2013, was a slow burner. Assembling the company in Kohat in November 1939 (at that stage I had to look up Kohat). Boarding a train to Bombay, and then, on 9th December sailing into the Indian Ocean on the Rajula and Talamba.

Wainwright recorded:

‘Lower animal decks (Rajula) reaching 93 F at night but animals kept fit by bringing up into fresh air’. Through the Suez Canal they went, reaching Marseilles on 26th December – Boxing Day to a Brit like me or Wainwright.

That was one of the points when the strangeness, the absurdity struck me. By this point I knew that the men were mostly Muslims. And that most of them had never been outside India before. So for me, 26th December had an immediate meaning, relating to the day-after-Christmas Day, a day for recovering after indulgence, perhaps with a country walk. A day spent with family, playing games and laughing, watching TV. These Indian soldiers had travelled thousands of miles from their homes, and were now in a strange continent, a strange cold climate, surrounded by people speaking strange languages. Of course this was their job, what they were trained and paid to do, but they were human too, and must have felt the strangeness so many times. What made it easier was – I’m sure – the buffering effect of their mates. Strangers together.

As I read on, the tension was building inside. I knew what was coming: the German attack of 10th May, but I didn’t known what would happen to this specific company of 300 or so. They travelled north, Wainwright wrote in pencil of the severe cold on the train “Weather snowey (sic) Water for animal at halts was slightly warmed & mules drank well”. The picture of innocents abroad was building.

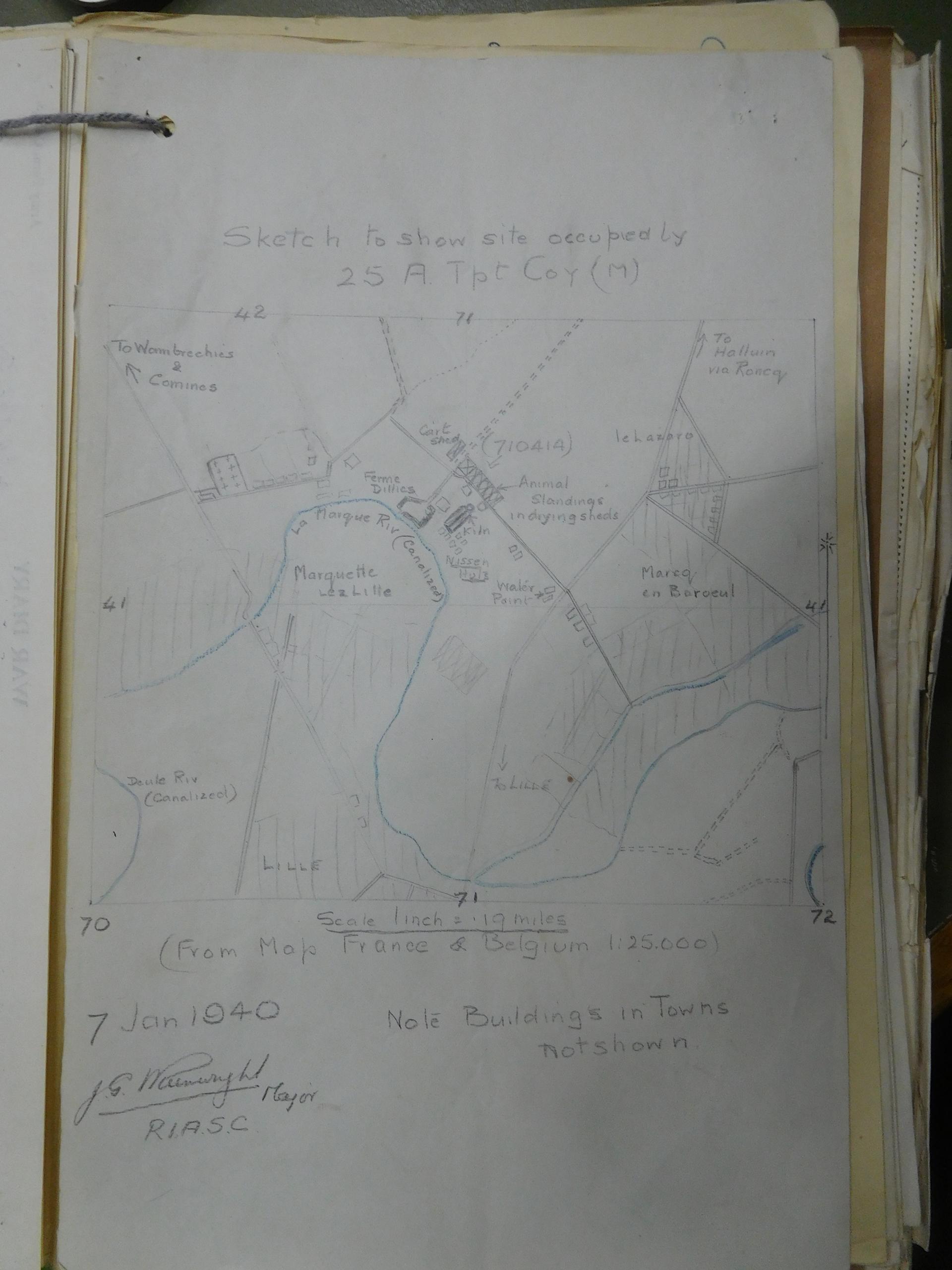

Sketch map of 25th Company area at Marquette-lez-Lille, by Wainwright

Unfortunately the diaries for March and April were missing, so the account leapt forward from the cold winter to the warm spring, just days before the blitzkrieg.

After 10th May the pace quickened, and I could read the emotions starting to come through. Wainwright was clearly frustrated by the lack of clarity when he wrote (on 26th May):

“CO reached unit having travelled 71 miles in search of orders. CO issued orders for mules to be freed & all stores and eqpt, except personal kit & equipment, and six days essentials of Indian rations to be left in situ’

I read on, as the men reached the beach on 28th May, and were evacuated safely that night.

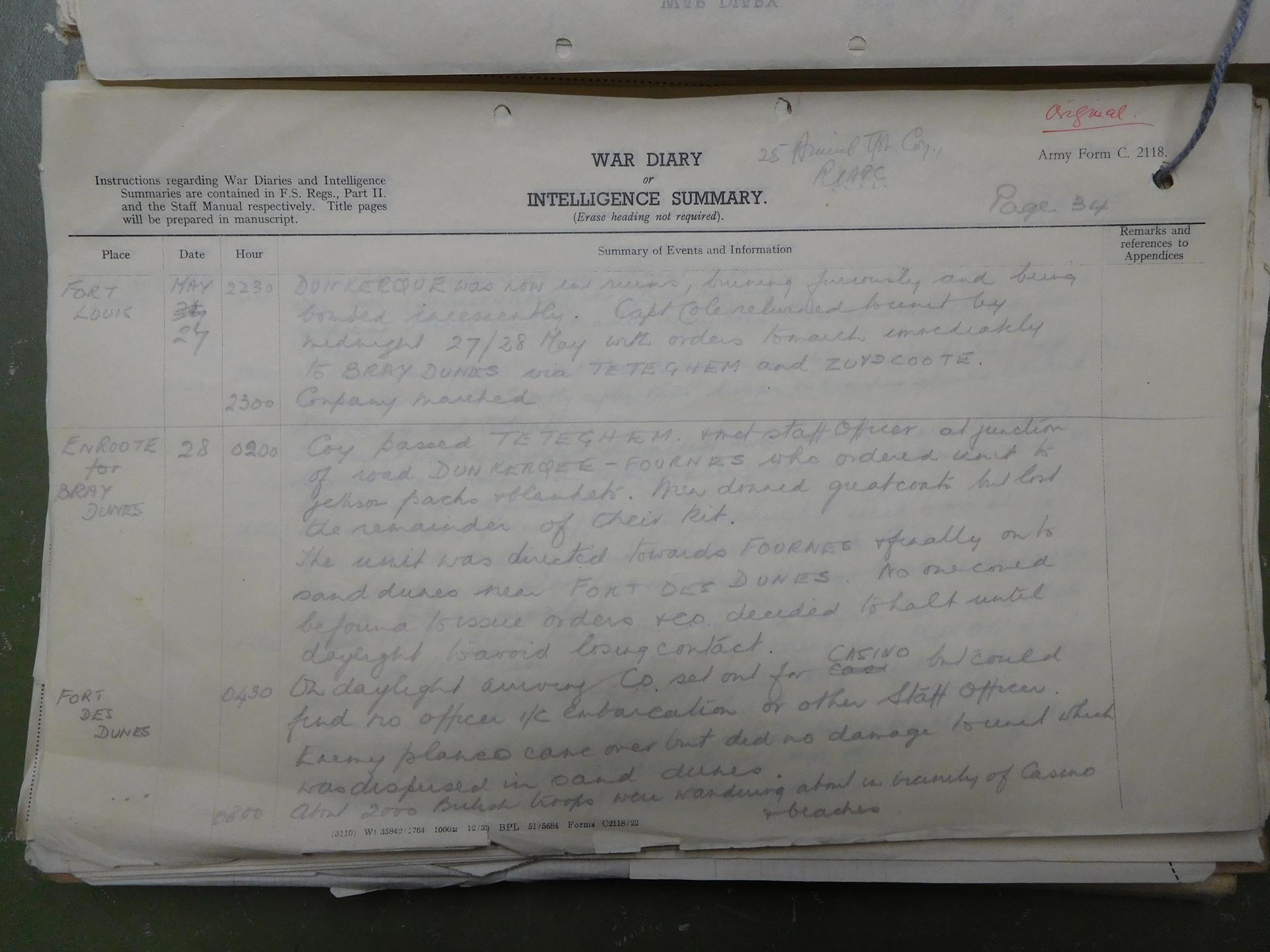

25th Company War Service Diary for 27th/28th May – arriving on the beach

On the morning of 29th May, Wainwright was at Dover and recorded:

“0900 This port was reached by 2 BO, 6 VCO, 210 IORs and 11 BORs between 0900 and 110hrs. These were immediately entrained & sent to various reception camps”

As I read this, sitting at the hexagonal table in the Archives, I was moved to tears. I knew that 338,000 British and French troops were taken off the beaches. Now I knew that a few hundred Indians were among them.

Why was this not known? I asked myself. And that’s when the germ of an idea was born. I could see that this was a great story – just the Dunkirk angle, without knowing about all the other amazing tales that were then in the future – and I wanted to be the person who told it.

The rest is history…

When that project ended, I was out of work and looking for something to do. While training on an ICA:UK course in Nottingham I had a dream in which I saw myself doing a PhD about the men of Force K6. Soon after that I registered for the History MA at Exeter University, despite having only a 2:2 BA in Drama from Hull, awarded in1983. Exeter accepted me, partly because of the TOSFOR work, and I started the Masters in September 2014.

At the social event on the first day I grabbed Dr Gajendra Singh, who I knew was an expert on the Indian Army. I think I rather surprised him! He agreed to supervise my dissertation.

By this point I had already spent 11 days in UK archives – the BL, TNA, IWM and NAM – and found lots of interesting documents, the Lamb painting of Akbar, and a host of photos in the IWM. I knew that I was on to something, and was continuously surprised that nobody else had written anything substantial about these men.

As the MA progressed I did my best to focus my modules towards India, Second World War and Empire. At Easter 2015 I started serious work on the dissertation, and widened my search. I visited the Woking Mosque, a significant K6 lieu de mémoire and met the son of a K6 man – Zubair Mohammed – who runs a local taxi firm. I went to the IWM documents store at Duxford in Cambridgeshire, and saw the amazing archive of Wilayati Akhbar Haftawari – the weekly newsletter produced just for these sepoys. And I made the pilgrimage to Llanfrothen in North Wales where I met the wonderful Giovanna Bloor, the first person I’d met who had actually met K6 soldiers during the war.

Giovanna Bloor (in trousers) as a land girl, shortly after the war

My MA dissertation was well received, and Gajendra suggested I apply for PhD funding, which I did. I continued my research during the year between finishing the Masters and starting the Doctorate, notably visiting Ashbourne and meeting the wonderful Betty Cresswell. In the summer of 2016, just before the PhD started, I went to Scotland. This visit was incredibly fruitful. I met Jo Meacock at the Kelvingrove Museum, and saw the painting of Abdul Ghani that would go on the book cover. I met Dr Nadeem Bhatti, who introduced me to the Glasgow Muslim community and Colourful Heritage. I met Hamish Johnston, who showed me round Strathspey. I visited Dornoch, Golspie and Lairg, all chock-full of stories, memories and photographs. Meeting Colin Hexley – son of Tom Hexley – was a real highlight, and he furnished me with a mountain of documents and photos, which proved extremely useful in reconstructing the story of the 22nd Company and their odyssey before and after capture.

Colin Hexley at Golspie Heritage Society

From September 2016 till September 2019 my full-time job was researching and writing about Force K6, as part of my PhD (I should record here my gratitude to the SWWDTP who funded the doctorate). During those three years I spent more than 60 days in archives. I visited France, Germany, India and Pakistan and found a phenomenal amount of relevant material.

I started to realise that this process was like a jigsaw puzzle where you don’t know the size of the puzzle nor the number of pieces not even what the picture is. And the pieces are scattered over two continents, some have been lost or even destroyed, some are deliberately hidden, and some (like the Helen McKie Waterloo station poster) are hiding in plain sight.

Without doubt, one of the highlights of the process was the visit to Pakistan in January – March 2018. Although I was frustratingly unable to get into most of the archives that I wanted to, I received lots of help from many quarters. Major-General Syed Ali Hamid (retd) – whom I had met briefly at the IWM the year before – was incredibly generous with his time, and introduced me to two key people – Anis Ahmad Khan’s daughter Zeenut, and Sabur, a retired Naik from the Pakistan Army, who knew all the villages of Pothwar and was able to find many relatives of K6 veterans. I was also able to meet many relatives of Major (later General) Akbar, who gave me interviews, photos and great hospitality.

Major-General Syed Ali Hamid in 2018

Finally on 16th September 2019 I handed in my PhD thesis. I was now free to write the book, the culmination of this seven-year process.

For my full list of thanks, please see the acknowledgements page.

The journey is by no means finished, however. I hope that the book and the press coverage will help people in South Asia and Europe to come forward and offer other memories. This website is here to help that process.

This book needs to be on the national curriculum. The kind of story that brings us together. It would be the perfect tribute to those who fought for our freedom.

- Adil Ray, actor, writer and broadcaster

The author

Ghee Bowman

Ghee Bowman was born in England in 1961. After careers in the theatre, education and the voluntary sector, he returned to university in 2014. He is married with two grown-up daughters, and lives in Exeter.

‘The Indian Contingent’ is his first book. His father WE Bowman wrote the noted spoof climbing book ‘The Ascent of Rum Doodle’.

Ghee is a story-teller, Quaker and a leader in the Woodcraft Folk, a voluntary youth movement for children and young people.

Acknowledgements

reproduced from the book ‘The Indian Contingent’

This book grew from my PhD at Exeter University, so I should first thank the South, West and Wales Doctoral Training Partnership who funded me. My supervisors Gajendra Singh and Padma Anagol gave first-class guidance and advice. Nicola Thomas has been a great encourager. My fellow PhD students have been wonderful: especial mention to Sonia Wigh, Cristina Corti for the maps and Sophy Antrobus for reading my drafts and being a chum. The University Pakistani Society were great for networking and the Digital Humanities Lab helped with digitisation of photos. This book was written on the top floor of the University Library, and all the library staff deserve medals.

I have built this story on the work of archivists and librarians in five countries, who provided access to my bread and butter (original documents) and have been friendly, helpful and supportive. Thanks to all of them, with a special mention to Jo Meacock at the Kelvingrove Museum in Glasgow.

The Indian Military History Society, through its journal Durbar, was a great source of contacts, and Chris Kempton provided useful input. The ‘Indian Armies of WW2’ Facebook group has answered many questions.

Around the UK I have listened to many stories about the boys of K6. Paritosh Shapland’s story is in many ways at the centre of this book, and he has been very generous with his time and his resources. Yaqub Mirza’s family gave me a great lift right at the end. Betty Cresswell told me of her family’s relationship with Uncle Gian, and kindly shared her photo album with me. The late Giovanna Bloor shared everything she knew. I will cherish the memory of a day spent in her cottage under the Cnicht mountain. Paul Watkins, Mark Ashdown, Geoff Sykes and Trilby Shaw helped me along the way. Hamish Johnston drove me around the Highlands and was a great source of information. Colin Hexley was very generous with material about his father, and Shirley Sutherland introduced me to him and others in Golspie. John Barnes and Peter Wilde in Dornoch, Joan Leed, Donny MacDonald and Marlyn Price in Lairg, Marion Smith, Catriona Spence, David & Sheena Macdougall in Kinlochleven, Stewart Mackenzie, George Milne and Donald Matheson in Loch Ewe were all very helpful and welcoming. In Glasgow, Nadeem Bhatti introduced me to the Colourful Heritage project and its staff Saqib Razzaq, Shazia Durrani and Omar Shaikh. In Woking, Mohammad Zubair gave me one of the best interviews ever, Zafar Iqbal aided my networking, the mosque was very welcoming and Rabyah Khan helped get me started. Katherine Douglass introduced me to the lovely people and the extraordinary story of Etobon.

I stand on the shoulders of giants. Rozina Visram is one such – anyone writing on the South Asian presence in Britain is in her debt. I shared beers and laughs with Lloyd Price, and treasure the friendship we developed in India. Many thanks to Yasmin Khan for writing the foreword.

I am a white British man writing a story about South Asians, which throws open many possibilities of cultural misunderstandings and errors. I am grateful to Sandhya Dave, Nazima Khan and colleagues at the Global Centre in Exeter for giving me confidence and helping me learn to step around a thorny area.

My time in Pakistan would have been fruitless without Major General Shahid Ali Hamid. He offered warmth, hospitality and boundless contacts. I am forever in his debt. My friend Omer Salim Khan (Omer Tarin) was supremely hospitable and generous during my visit to Abbottabad, and even more so afterwards, commenting on the draft manuscript. Jawad Sarwana drove me round Karachi and introduced me to the wide and warm family of General Akbar, and Imran and his daughter Mahin were particularly generous with time and photos. Zeenut Ziad gave me two interviews, when her parrot would let her. Khizar Jawad was incredibly helpful in Lahore. Brigadier Asim Iqbal of the Army Service Corps gave a late rush of help. Above all, Jenny, Marcel and Luqman ensured I had a safe secure base in Islamabad, Sabur was a wonderful fixer who seemed to know everyone in the Potohari villages, Waheed drove us round those villages and Waqar Seyal was a fantastic translator and interpreter. In India, Shachi and Naveen made me welcome and helped me with my first steps in Hindi/Urdu and Rana Chhina at the United Services Institute in Delhi was extremely helpful.

For permission to use quotes, thanks to Hackett Publishing Company for the quotation from Philip Ivanhoe’s translation of Daodejing of Laozi, and to HarperCollins India for the two quotations from Raghu Karnad’s Farthest Field.

I appreciate that I haven’t included all the great stories that I heard during my research. If I’ve missed yours out, apologies. If I haven’t heard it yet, please get in touch. All errors in memory or interpretation are entirely mine.

Three people helped and inspired this writing process. My father Bill Bowman showed the way. Clare Grist Taylor believed in me and this story and gave many practical tips. My editor at The History Press, Simon Wright, was always encouraging, constructive but firm.

Three other people made it possible. My daughters Alex and Hannah helped enter hundreds of names in the database, encouraged me and (in Hannah’s case) did translations from French. Above all, my thanks and love go to my wife Rebecca. She has supported me and fed me all the way through. A wiser partner would be impossible to find.

An incredible and important story, finally being told.

- Mishal Husain

Force K6

Website credits

Technical consultant

Alex Michel-Bowman

Urdu translation

Waqar Ahmed Seyal

Hindi translation

Sonia Wigh